For one of my sociolinguistics classes, I was tasked with a research project for the term. Below is my report, adapted for this page. This report is preliminary and has a small sample size and is an early work of mine.

Introduction

In the modern business landscape, the United States serves as a hub for many industries, with icons including Wall Street for financial services and Silicon Valley for technology and entrepreneurship. This exposure has influenced various Spanish speaking regions of the world. Mexico, especially, is prone to borrowing from English due to the country’s close proximity and significant business integration with the United States.

Beletskaya (2018) finds two types of English borrowings in Business Spanish important for this analysis: necessary neologisms and luxury neologisms. The former is a necessary new addition to the language introduced because no other similar terms previously existed, whereas the latter is used to signal prestige and have an existing Spanish equivalent. For example, Beletskaya (2018) finds that “joint venture” is a necessary term, while “cash flow” has the Spanish counterpart “flujo de caja,” making it a luxury term. While this is an important distinction, there does not seem to be much further insight into how luxury neologisms are socially stratified with respect to class and occupation. The findings suggest that startup culture and online content creators favor luxury neologisms (though the luxury neologisms adopted by each group are different), whereas academic discourse has a preference for Spanish alternatives and avoids luxury neologisms.

This paper will focus on luxury neologisms to further explore how and why different groups–academics, startup corporations, and online video creators–choose to use English borrowings or their corresponding phrases in the discussion of business topics. My research will analyze both speech in business-related YouTube videos, from educational to company pitches.

Methodology

This study examines the speech patterns of individuals from three distinct groups: academia, corporations, and digital content creation. These groups were selected based on their varying degrees of formality in engagement with English luxury neologisms. Academics adhere most to formal linguistic norms, followed by the professional context of startups, while digital content creators typically are not held to the same high standards of formality. Higher levels of formality are associated with more prescriptive beliefs, which in turn shapes linguistic choices and usage of English neologisms depending on the expected level of formality.

Research data was collected through publicly accessible YouTube videos and associated websites. Content selected for analysis relates to business-related topics, including entrepreneurship and finance. A video, spanning approximately 10 minutes, was analyzed from each group. The academic video was titled “Algunos conceptos básicos de economía” and was authored by Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas UNAM. The startup video was titled “Su negocio es CUIDAR tu salud 😷🤑”, authored by Shark Tank México. The content creation video was titled “Hacer Dropshipping en México 2025: 3 Opciones que Funcionan”, authored by Edgar R. Ramirez. Data collection was supplemented by YouTube’s automatic captions. Due to difficulties sourcing videos for specific topics by Mexican creators, I limited analysis to one creator, so there may be a misrepresentation of the groups analyzed. Additionally, as a non-native intermediate Spanish speaker, I may have missed some occurrences of luxury neologisms.

The analysis focuses exclusively on luxury neologisms, as defined by Beletskaya (2018). Data was collected for each luxury neologism used (or lack thereof). Included with the luxury neologism are the English equivalent, the Spanish traditional equivalent phrase or luxury neologism equivalent phrase (contingent on if an alternative phrase was used), an example of the luxury neologism used in Spanish discourse if it was not used in the video, and a timestamp.

Findings

Academia

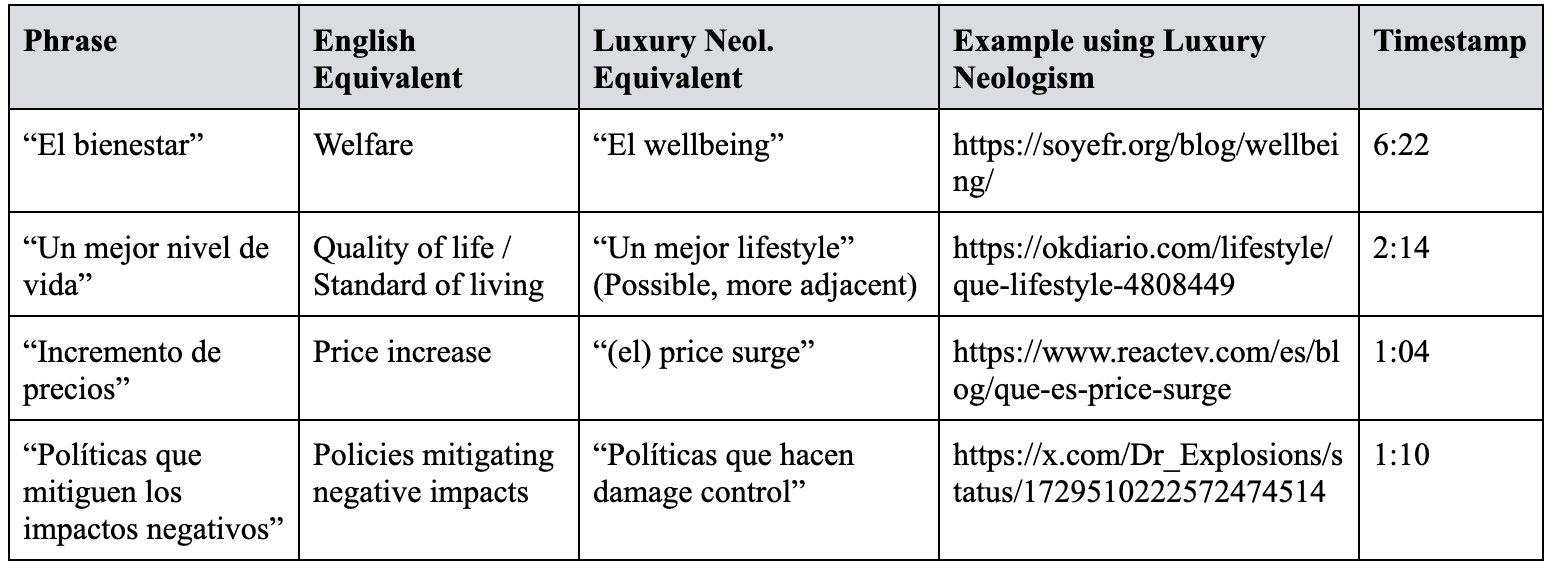

In UNAM’s academic videos, no instance of luxury neologisms were found, and every time an opportunity for one of these terms was present, the speaker opted to use the Spanish equivalent. The speakers in the first video, titled Algunos conceptos básicos de economía, had opportunities to use luxury neologisms, but instead opted for Spanish equivalents, as noted in the following table:

The first video is a rather informal Question and Answer (Q&A) style video, where someone asks a question and an expert explains it. To account for potential miscounting of non-academics for the purposes of this report, only the speakers who answered questions were examined as they are verified experts. However, even in this slightly more informal setting, the experts have no instances of adopting any loanwords that meet Beletskaya’s definition of Luxury neologisms and only use traditional Spanish equivalent phrases.

I hypothesize that this phenomenon stems from the desire of Spanish language authorities, such as the Real Academia Española (RAE), to limit the official recognition of English loanwords to prescriptively “cleanse” the language. The RAE has recognized English luxury neologisms, but this recognition is done whilst promoting a Spanish equivalent. For example, the RAE recognizes “cash flow,” but does so in the “Diccionario panhispánico de dudas” (DPD) and its entry discusses how the phrase should not be used for the more prescriptively acceptable “flujo de caja” (Real Academia Española n.d.).

Professional academic institutions such as Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, the producer of the academic content, are more likely to follow stricter linguistic norms than the average person, potentially leading to the lack of luxury neologisms in the videos. However, other factors may have also contributed to this decision. For example, these luxury neologisms may have different connotations compared to the standard Spanish version. Even in English, “price surge” has a more powerful connotation compared to “price increase.” Additionally, people outside of specific speech communities may be unfamiliar with some of these luxury neologisms, so the exclusion of any of these words may be for accessibility or relatability. Beletskaya’s luxury neologisms developed for prestige purposes, and, as education institutions are for public good, adopting these luxury loanwords may leave viewers perceiving the institution in a worse light. This is especially the case in the first video, which is of experts trying to simplify explanations of terms for a beginner level audience, a scenario where using luxury neologisms to enhance credibility would be even more inappropriate and unwelcoming. These factors may contribute to academia’s hesitation to adopt these luxury neologisms, even though they may add to credibility in some circumstances.

Startup Corporations

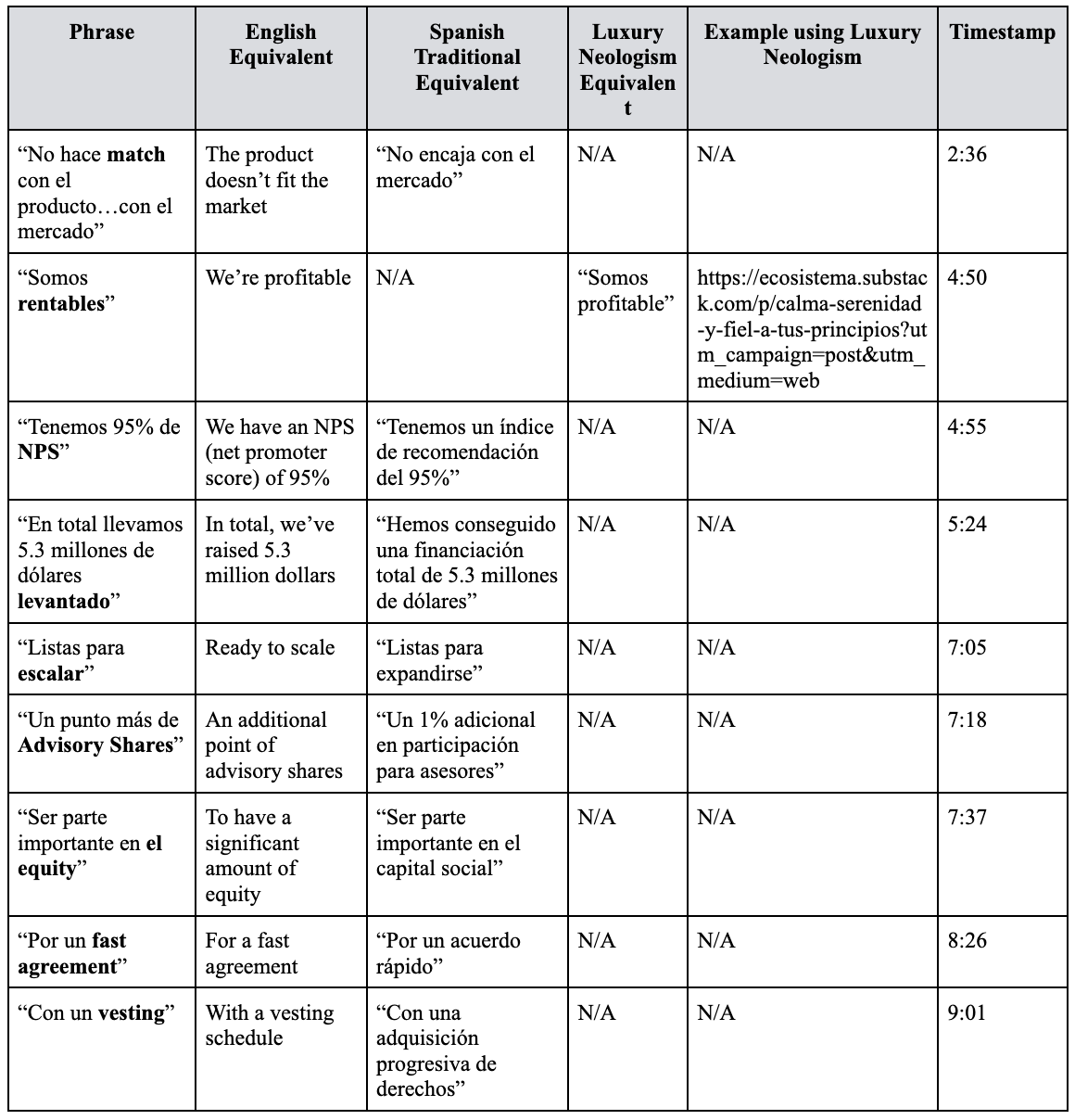

In the videos from Shark Tank México, Mexican startups were pitching to “tiburones” (sharks), or investors who would fund their companies for a percentage of their ownership. In this video, there were two pitches. The table below showcases the videos’ findings:

The situation of startups pitching is ideal for observing luxury neologisms because it places pressure onto the entrepreneurs pitching their ideas. As luxury neologisms are used often to signal credibility and for prestige reasons, entrepreneurs are more likely to adopt them under these circumstances. While this does showcase different types of neologisms, startups pitching to investors may warrant speech patterns that are different from internal communication. For example, it may be possible that internal communication within startups use less luxury neologisms and more Spanish equivalents because they have less of a desire to impress, but analysis of this is outside of the scope of this report due to difficulty of attaining internal communication in startups.

In the data, luxury neologisms were actively used at a high frequency with phrases including “match,” “el equity,’ and “un fast agreement,” among others. These code-switching tactics are done to signal to the “tiburones,” or the potential investors to their company, that the team is well-versed in startup culture and is therefore worthy of investments. These words may signal these attributes because of the influence that English has on the linguistic marketplace for business communication due to the United States’ global influence. Furthermore, this attribute may be exemplified due to the close proximity of Mexico to the United States. The United States is a significant entrepreneurship hub with Silicon Valley and other regional ecosystems that foster innovation and startup culture, which develops specific language patterns that have influenced startup speech habits in Mexico. The most obvious borrowings are the non-adapted anglicisms that keep their original orthography and pronunciation, including “equity,” “vesting,” “fast agreement,” and “Advisory Shares.” These non-adapted anglicisms are all nouns, which shows that noun luxury neologisms are more likely to be unchanged when borrowed from English. Nouns usually have to go through minimal morphological changes compared to verbs when borrowing between languages and do not have to be modified as much. This results in noun luxury neologisms’ easy identification in Spanish. There is also a possibility that nouns seem more foreign, and thus these nouns may seem more prestigious compared to verb counterparts.

On the other hand, the verb and adjective luxury neologisms used in the pitches seemed more adapted and calqued to Mexican Spanish compared to the nouns. For example, when the entrepreneurs used luxury neologisms for “ready to scale” and “raised 5.3 million dollars,” they used calques, or literal translations of the English phrases. “Listas para escalar” translates literally to “ready to scale” and “en total llevamos 5.3 millones de dólares levantado” translates literally to “in total, we have 5.3 millions of dollars raised.” These phrases may seem like they are not a luxury neologism, but Spanish syntax makes borrowing verbs directly much more challenging compared to nouns, making calquing the terms a better option than borrowing pre-existing Spanish verbs. However, as there are still traditional Spanish equivalents for these calqued phrases, the terms are still luxury neologisms and add prestige over the solely Spanish form. This finding suggests that, although more English-sounding borrowings add more prestige to luxury neologisms, there are sometimes necessary modifications to adapt prestigious forms into Spanish. These adapted forms are still luxury neologisms because they are designed to increase the speaker’s social status and integrate themselves closer to English startup speech patterns.

Interestingly, the speakers still had some instances where they opted out of using these luxury neologisms for the traditional Spanish equivalents. There were two instances where this happened: “tenemos un trato” for “we have a deal” and “somos rentables” for “we’re profitable.” The inclusion of regular phrases instead of luxury neologisms suggests that Mexican Business Spanish does not add prestige to some phrases swapped for luxury neologisms. For example, “tenemos un trato” and “somos rentables” are much more general and more commonly used phrases compared to “fast agreement” and “el vesting,” where luxury neologisms were used for more specialized business terminology that is not as commonly used as “we have a deal” and “we’re profitable.” This suggests that more common phrases that are used in business discourse across the world are less likely to be swapped out for loan words, as the phrases are embedded and unlikely to change. Using “temenos un deal” and “somos profitables” may feel more forced compared to their Spanish counterparts due to the high frequency of the phrases. This could be because more specific phrases call for more authority, leading to luxury neologism usage, while more common phrases are more casual and swapping in a luxury neologism would be awkward.

Content Creator

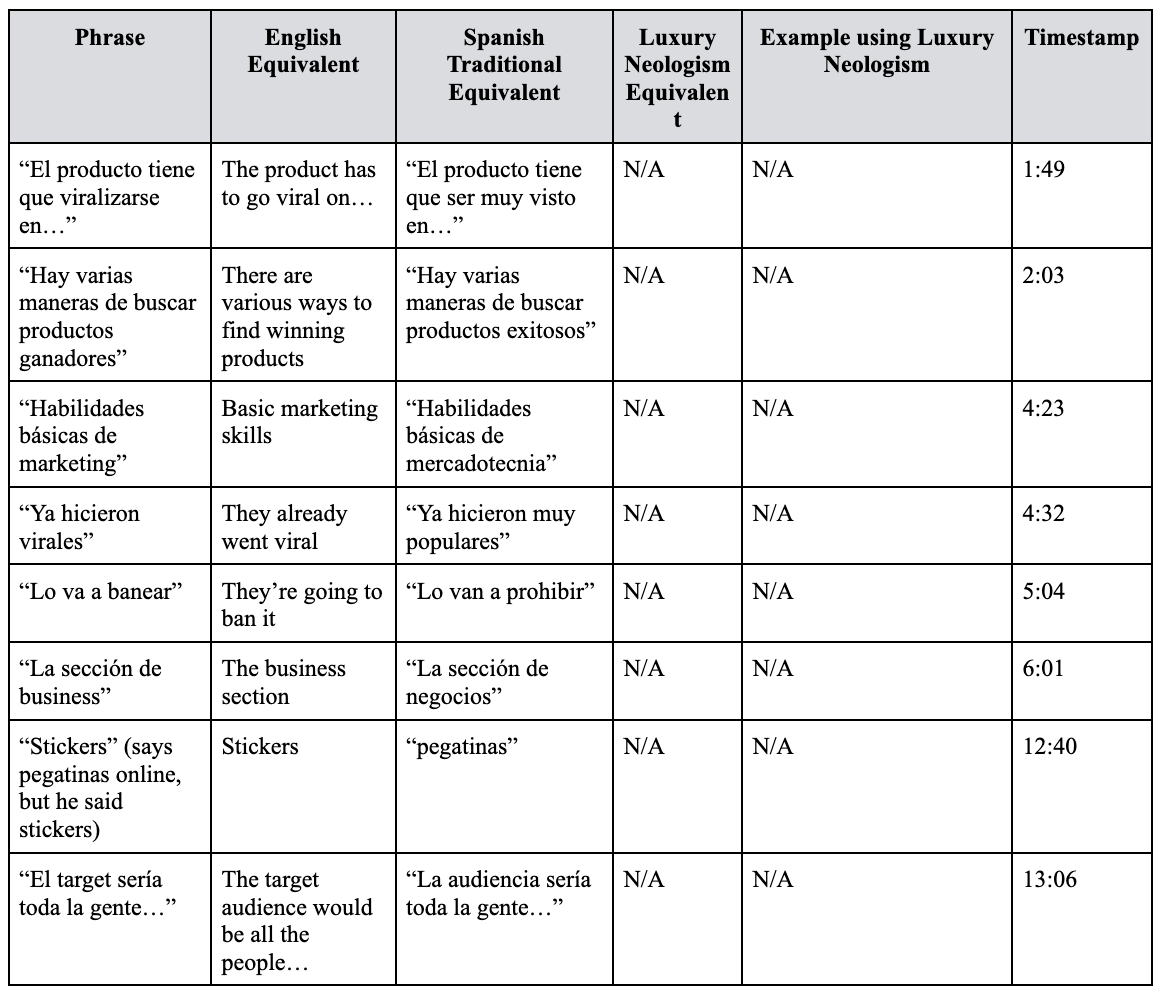

For the content creator, I analyzed the speech habits of an online guru who has built a living off of creating YouTube videos. The video is targeted at people interested in starting their own businesses and serves as a tutorial for “dropshipping,” a popular type of business model that one person can easily start from their computer. The table below shows the findings:

The online guru trends towards using luxury neologisms in most instances, but there are some things to take into consideration. This video is a tutorial targeted at beginners to teach them dropshipping, which is a business model with a low barrier to entry. This restricts heavy jargon usage, as implementing too much may alienate his viewership. However, at the same time, the speaker must build credibility and authority, leading to implementation of luxury neologisms for this purpose. The only luxury phrases he uses are widely known: viralizarse, marketing, banear, business, and stickers. This is in contrast to the entrepreneurs on Shark Tank México that utilized more specific and niche business terms as luxury neologisms including vesting, and Advisory Shares to signal their status as an insider in business language and culture.

Additionally, a lot of these luxury neologisms this speaker uses bring “in group” status outside of business contexts within digital and youth cultures. For example, using “stickers” instead of “pegatinas” could come from a more youthful origin compared to formal marketing and business jargon. In the same way, “viralizarse” and “virales” are luxury neologisms that have been popularized by content creators on platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok, who tend to be younger. These luxury neologisms do not show business expertise, but rather knowledge in internet culture, which is probably extremely valuable for the creator because their target audience consists of younger people who want to get into business. Incorporating these internet luxury neologisms alongside more accessible business luxury neologisms including “business” and “marketing” further reinforces the creator’s credibility in both internet culture and business. The speaker also presents in a way that remains accessible to his audience by not using complex words that the general public and his target audience does not understand.

Conclusion

Usage of English Luxury neologisms in Business Spanish greatly varies depending on the context of the business discourse. In more academic situations, using luxury neologisms is not done because of the stricter linguistic norms that academics and higher education institutions must adhere to. Additionally, academics are already verified as experts, so they may no longer feel the need to implement these neologisms to increase their credibility. Contrarily, entrepreneurs and startups tend to heavily rely on English luxury neologisms, likely due to Silicon Valley and English startup culture’s influence on Mexican startups and a desire to appear credible. As such, Mexican entrepreneurs tend to use more technical luxury borrowings including “Advisory Shares” and “vesting.” Similarly, online content creators tend to use luxury neologisms to build their credibility. However, these creators seem to only adopt more basic luxury neologisms to avoid alienating their audience. For example, the creator I analyzed used “business” and “marketing” for business luxury neologisms, but also incorporated internet-specific luxury neologisms such as “viralizar.”

How a speaker incorporates luxury neologisms seems to reflect their social standing, revealing that this adoption is based on social factors. It can also reflect the speaker’s goals in speech and how they wish to be perceived; Guy (2011) states that language has sociosymbolic aspects that identify speakers as part of a group, or having a particular social identity. Additionally, as academics tend to be older, and startup founders and video content creators tend to be younger, there is also a possibility that luxury neologism adoption has some correlation with the speaker’s age. However, this is inconclusive with the evidence I gathered, as age correlates with status. Nevertheless, as English continues to be a dominant language in the business world, these luxury neologisms raise questions about the future role of prescriptive entities such as the RAE. Currently, the RAE recognizes some of these luxury neologisms, but advises against using them. As they grow in popularity, however, it will be interesting to see how the RAE and other prescriptive entities, as well as academics, react.

References

Beletskaya, O. S. 2018. Classification of English loanwords in Business Spanish. Training, Language and Culture, 2(2), 81-94. doi: 10.29366/2018tlc.2.2.6

Guy, Gregory R. 2011. “Language, Social Class, and Status.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Sociolinguistics, edited by Rajend Mesthrie, 160. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas UNAM. 2023. “Algunos conceptos básicos de economía.” YouTube video, 7:55. Uploaded 11 Sept. 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LdD0cZwF0ho&ab_channel=InstitutodeInvestigacionesEcon%C3%B3micasUNAM.

Ramirez, Edgar R. 2024. “Hacer Dropshipping en México 2025: 3 Opciones que Funcionan.” YouTube video, 14:52. Uploaded 17 Dec. 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YvRIvyGps8o&ab_channel=EdgarR.Ramirez.

Real Academia Española. n.d. "Cash flow." Diccionario panhispánico de dudas. https://www.rae.es/dpd/cash%20flow.

Shark Tank México. n.d. “Su negocio es CUIDAR tu salud 😷🤑 | Temporada 9 | Shark Tank México.” YouTube video, 9:38. Uploaded 8 Apr. 2025. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5fD3aL_FEFc&ab_channel=SharkTankM%C3%A9xico.